Boston Tea Party

The Event: The boarding of British ships and dumping of tea in Boston Harbor by Boston merchants disguised as Mohawk warriors

Date: December 16, 1773

Place: Boston, Massachusetts

Significance: This dramatic act of rebellion became an important symbol of American dissatisfaction with Great Britain’s colonial economic policies, particularly the imposition of taxes without granting colonists representation in Parliament, and helped lead to the American Revolution.

Before 1767, most residents of the British American colonies drank smuggled Dutch tea rather than pay the high British tax on tea. The Townshend Acts of that year, named for Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer, lowered the tax but made more efficient the collecting of it. Townshend’s power to collect taxes was enhanced by the illness of the prime minister, which allowed Townshend to become the functional leader of the government. Many Americans continued to boycott British tea, demanding the removal of all import taxes.

By 1773, the British East India Company had a surplus of seventeen million pounds of tea. The company faced bankruptcy as the value of its stock dropped by almost one-half. On May 10, 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act as a means of saving the British East India Company. This act lowered the tea tax but granted the company a virtual monopoly on the tea trade to America, allowing it to sell directly to select American consignees. The consignees in Boston included two sons and a nephew of Thomas Hutchinson, the royal governor of Massachusetts.

Three tea ships arrived in Boston Harbor in late November. Other merchants demanded the resignation of the consignees who were to handle the tea for the British East India Company. The consignees in Philadelphia and New York eventually complied, but those in Boston refused. By November 30, people had gathered in mass meetings in Boston, demanding that the tea be returned to England, but Governor Hutchinson refused to comply.

On the evening of December 16, another mass meeting, chaired by Sam Adams, was held at Boston’s Old South Church. After being informed of the governor’s final refusal, Adams gave the signal for three companies of fifty men each, dressed as Mohawks, to board the three ships and dump their tea into the harbor.Working throughout the night, the men dumped 342 chests of tea. No other property on the ships was damaged. British warships anchored nearby made no attempts to intervene.

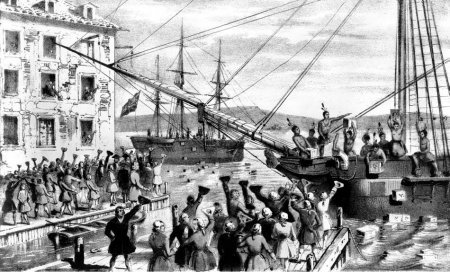

This 1864 lithograph shows people cheering as tea is dumped overboard in Boston Harbor in 1773. (Library of Congress)

Similar events took place in Charleston, South Carolina. On December 2, another tea ship, the London, had arrived in Charleston Harbor. A mass meeting led to the resignation of the Charleston consignees. The London’s tea was seized on December 22 and stored in government warehouses until July, 1776, when it was sold to raise funds for the revolution.

To punish Boston for leading the colonial defiance of British policy, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts of 1774-1776, which closed the Port of Boston and reduced the level of autonomy of Massachusetts. However, these actions only increased the colonists’ resolve to take control of their own destiny.

Glenn L. Swygart

Further Reading

Burgan, Michael. The Boston Tea Party. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2000.

Zinn, Howard, and Anthony Arnove. Voices of a People’s History of the United States. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2004.

See also: Chinese trade with the United States; Colonial economic systems; Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company; Parliamentary Charter of 1763; Revolutionary War; taxation; Tea Act of 1773.