Farm subsidies

Definition: Supplemental income paid to American farmers by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for commodities such as wheat, corn, soybeans, cotton, and rice in an effort to manage supply and control prices

Significance: Farm subsidies help control the price of crops, ensure farmers of a consistent income, and keep the United States free from dependence on foreign countries for its food supply.

During the 1930’s, the United States had 6 million farms on which one-quarter of the population lived. However, by the end of the twentieth century, only 2 percent of the population resided on the nation’s 157,000 farms. Various United States farmbills, dating back to the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, supplement the income of growers and producers of more than twenty commodities, including sugar, wheat, rice, peanuts, soybeans, dairy products, tobacco, wool, honey, and vegetable oils. These agricultural subsidy programs, which amount to more than $25 billion annually, ensure that farmers receive a base minimum price, called a price floor, for their crops, as well as a financial supplement that is funded by tax revenues. For instance, if farmers receive $3.50 for a bushel of wheat on the market, the government might pay them an extra 50 cents per bushel to ensure a certain level of payment. These programs, created by farm bills, are the subject of great controversy.

The Pros and Cons

Those who favor farmsubsidies believe that farmers could not compete with low-priced foreign imports unless they received subsidies. They would be bankrupted and lose their farms, and American agriculture would all but disappear. Consequently, the United States would become dependent on other countries for its food supply, and this would severely upset the nation’s balance of trade. Some argue that farm subsidies are vital because although farmers have a large capital investment and therefore high fixed costs of production, weather can produce severe fluctuations in crop yield. When weather reduces production levels, the market price goes up, but farmers have less to sell, and their income would drop if not for subsidies. When weather boosts production, the market price falls, and farmers would make less if not for subsidies. Farm subsidies mean that food and animal producers pay less for crops (as the government makes up the difference), ensuring that lower-income people, who spend a higher percentage of their income than do wealthier people on food, are able to afford to purchase groceries. Farm subsidies, partly by encouraging overproduction, also allow U.S. agricultural products to be competitive exports.

Some Americans insist that subsidies are simply against the principles of free trade and are angry that their tax dollars are spent on farm subsidies. They believe that farmers should not rely on government financial support and look on farm subsidies as a costly form of welfare. Consistent income for farmers, they insist, should be maintained through insurance programs and the futures market. Besides, the argument continues, the image of the poor single-family farm is out of date. These critics argue that, in the twenty-first century, much farming is done by agribusinesses or large farming operations. Subsidies, critics insist, go mostly to the biggest, most productive farms, which simply do not need them. Farmers, they insist, will grow anything, even if it is not demanded by the public, just to get the subsidies.

Critics also assert that providing farmers with subsidies causes problems in the proper allocation of resources. For instance, instead of using land as pastures for cattle, farmers grow corn to use as livestock feed. Also, subsidies encourage farmers to grow corn for conversion to ethanol, which is used as automotive fuel, instead of for food.

Beyond the question of whether crops should be subsidized, a serious question remains as to which crops should be subsidized. Because 90 percent of subsidy money goes to corn, wheat, soybeans, and rice, those are the cheapest and most abundant crops produced. These crops are often used as feed for cows, pigs, and chickens, thus supporting the dairy and meat industries. Fresh vegetables and fruit, by contrast, are not significantly subsidized. Thus, many less nutritious foods are lower priced in American supermarkets and fast-food restaurants, whereas fresh, nutritious food is more difficult to afford. Were subsidy money to be reallocated, this situation could be reversed.

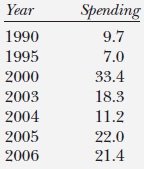

Government Spending on Farm Income Stabilization, 1990-2006, in Billions of Dollars

Source: Data from the Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2008 (Washington, D.C.: Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census, Data User Services Division, 2008)

World Markets

The World Trade Organization has determined that keeping the price of food low through the use of export farmsubsidies can help American farmers while providing low-priced food for people in developing countries. However, these same export subsidies also encourage these poorer countries to remain dependent on food from wealthier countries. They can in fact ruin poorer farmers and force them off their land, thus contributing to an increase in poverty. For example, it is estimated that 2 million Mexican agricultural laborers have been forced off their land by the combination of American corn subsidies and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

In 2008, however, the problem was not excess supply of grains and oilseeds (including soybeans) and low prices but rather high prices and increasing demand. Low agricultural productivity in the poorest countries, higher cost of agricultural production (higher fuel costs), diversion of corn and other grains to make biofuels, droughts in Australia and Europe, and rising populations and incomes have caused commodity prices to rise and created worldwide food shortages. These shortages were felt most in the poorest countries, which could no longer afford to import food, but were also evident in the prices Americans paid for food. The food consumer price index, created by the U.S. Department of Labor, rose at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 7.5 percent for the first eight months of 2008, compared with 4.9 percent in 2007.

M. Casey Diana

Further Reading

Ikerd, John E. Crisis and Opportunity: Sustainability in American Agriculture. Winnipeg, Alta.: Bison Books, 2008. Collection of essays dealing with the sustainability of food and farming systems. Penetrating discussions of the results of farm subsidies.

Pawlick, Thomas F. The End of Food: How the Food Industry Is Destroying Our Food Supply—And What We Can Do About It. Fort Lee, N.J.: Barricade Books, 2006.Written by an investigative science journalist and professor of journalism; uses scientific research that demonstrates the negative effects subsidized crops can have on the food supply of the United States.

Pollan, Michael. “The Way We Live Now: You Are What You Grow.” The New York Times, April 22, 2007. Pollan blames the rising rate of American obesity on the overabundance of junk food brought about by the wrong kind of farm subsidies.

Pyle, George B. Raising Less Corn, More Hell: Why Our Economy, Ecology, and Security Demand the Preservation of the Independent Farm. New York: Public Affairs Press, 2005. Veteran journalist Pyle argues that American farmers can feed the world by growing fewer crops and that growing too much food contributes to world hunger, because farmers in developing countries cannot compete against subsidized American food.

Roberts, Paul. The End of Food. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2008. Roberts, author of The End of Oil, makes a plea for rethinking food systems by analyzing the global food economy and the effect of farmsubsidies worldwide, especially on the poor.

See also: agribusiness; Cereal crops; cotton industry; Dairy industry; Farm Credit Administration; farm labor; Farm protests; government spending; Rice industry.