Pullman Strike

The Event: Strike held by Pullman Palace Car Company workers during the strained economic times of the Panic of 1893

Date: May-July, 1894

Place: Chicago, Illinois

Significance: The Pullman strikers not only received better wages as a result of the strike but also were successful in affecting economies in the majority of states throughout the union.

During the early 1880’s, George Pullman, founder of Pullman Palace Car Company, constructed a town named Pullman for his workers. The amenities and seeming convenience of this town made the factory owner seem glorious in the eyes of his workers. However, when the Panic of 1893 negatively affected the nation’s economic climate, life became brutal for Pullman’s residents.

Between July and November of 1893 alone, more than three-quarters of the Pullman workforce was laid off. For those who remained, work was harder but wages were no higher. On December 9, 1893, the workers struck, and although they had begun to unionize in early 1891, the number of unionized workers was not enough to make the strike effective. As a result, the December strike lasted only a few days.

In 1894, the economic situation worsened for Pullman workers. They continued paying high rents for their residences and inflated prices for goods, without a pay increase. When their attempts to obtain better wages failed, they struck on May 11, 1894. This strike is known as the Pullman Strike.

In between the short strike in December, 1893, and the large strike in May, a significant portion of the workers had joined the American Railway Union (ARU), a new union that had formed in the spring of 1894 under the leadership of Eugene V. Debs. Through the auspices of ARU, the strike literally stalled state economies across the United States. Pullman responded to the strike by leaving Chicago under the cover of night and moving to his summer home in the east.

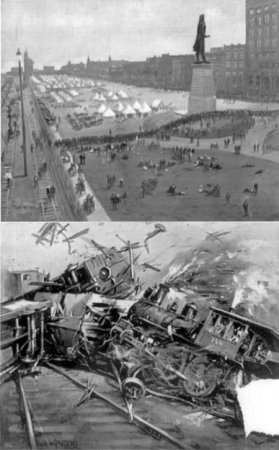

Magazine illustrations showing U.S. troops camped on the lake front (top) and freight cars and an engine wrecked by rioters at Kensington, near Pullman, in July, 1894. (Library of Congress)

Although Pullman refused to listen to the complaints of the workers, Debs and theARUupped the ante by securing a boycott of all Pullman cars throughout the United States in late June, 1894. Because of the ubiquity of Pullman cars, this boycott stopped rail service throughout the midwestern states. In response to the boycott, railroad executives had nonunion railway workers attach U.S. mailcarrying- cars to trains that had been boycotted, thus forcing the federal government to intervene to secure mail delivery. In July, 1894, President Grover Cleveland sent approximately 12,000 U.S. troops to break the strike and ensure that mail would be delivered. Cleveland’s actions ended the strike.

A. W. R. Hawkins

Further Reading

Burgen, Michael. The Pullman Strike of 1894. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2008.

McMath, Robert C. American Populism: A Social History, 1877-1898. New York: Hill & Wang, 1993.

Summers, Mark Wahlgren. The Gilded Age: Or, The Hazard of New Functions. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1997.

See also: Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; labor history; labor strikes; Panic of 1893; Postal Service, U.S.; Railroads; Randolph, A. Philip; Supreme Court and labor law.