Antitrust history

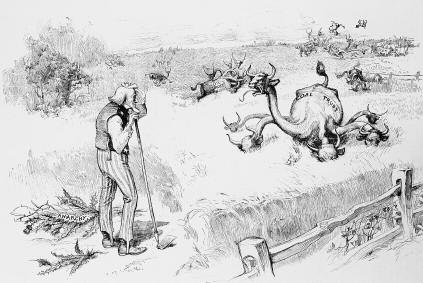

Characterizing the process of reviewing MERGERS to decide whether they violate antimonopoly laws. The name derives from the period of trust creation in the United States, from 1875 to 1911, when many large “trusts” were formed in order to consolidate various industries by merging companies in similar lines of business. The trusts eventually gave way to the modern HOLDING COMPANY, but the term antitrust survives, dating from the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890.

The SHERMAN ACT was the first major antitrust legislation passed in the United States. Previously, the only way to attack monopoly in the courts had been through the COMMERCE CLAUSE in the Constitution, which brought mixed results because of its limited potential applications. After the act was passed, trust creation continued, and a record number of mergers were consummated during the McKinley administration in the late 1890s. But after Theodore Roosevelt became president, more antitrust cases were mounted, initiated by the Justice Department. Actions were initiated against the Northern Securities Company, American Tobacco Company, Standard Oil Company, and the United States Steel Corp. among others. The first decade of the 20th century became known as the golden era of antitrust.

Two of the most notable antitrust cases— against Standard Oil and American Tobacco— were upheld by the Supreme Court in 1911, and both companies were ordered to be broken up. In 1914, more antitrust legislation was added when Congress passed the CLAYTON ACT in an attempt to prevent price discrimination, interlocking directorships, and vertical mergers, topics not specifically covered by the Sherman Act. The Clayton Act prohibited companies from acquiring the stock of others in order to prevent competition. Like the Sherman Act, the law was vague in places and did not always prevent horizontal combinations from taking place. Congress also created the FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION (FTC) in 1914 to help prevent price discrimination and protect consumers by issuing cease and desist orders against companies that had complaints filed against them for unfair trade practices. The agency was intended to enhance the Sherman Act and give the government a method of preventing unfair practices short of filing suit under the 1890 legislation. Today antitrust actions on the federal level can be initiated by the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department or the FTC.

Antitrust laws were complemented by antitrust policy, as seen in the political attitude of the administration holding office toward big business and mergers in particular. In some cases when administrations in office were friendly to business, as in the case of McKinley, mergers were allowed to proceed at a rapid pace. In other cases, such as the administration of Theodore Roosevelt, “trust busting” was in vogue, and many cases were brought before the courts in keeping with the administration’s progressive leanings. During the 1920s, another burst of mergers occurred as successive Republican administrations did not pursue antitrust in the courts, especially after U.S. Steel was ruled a “good trust” by the Supreme Court, ending a decade-long court fight in favor of the company. The friendly attitude toward mergers lasted until the NEW DEAL.

Antitrust policy was given a boost during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s second administration when Thurman Arnold of the Yale Law School was named head of the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department. The staff and budget of the division were increased dramatically, and new cases were pursued. During the first FDR administration, antitrust laws had been relaxed in favor of pursuing economic recovery during the Depression, but another RECESSION occurred in 1937 that convinced many in the administration that business was to blame. Stronger antitrust actions followed. An inquiry into industrial concentrations in 1939, investigated by the Temporary National Economic Committee (TNEC), discovered that many major industries were dominated by a few large firms, despite previous attempts to level the playing field. But after the outbreak of World War II, antitrust activity again fell as economic activity concentrated on the war effort. The one law that was passed during the 1930s—the ROBINSON-PATMAN ACT (1936)—was aimed mostly at the expansion of CHAIN STORES and did not have any substantial applications until after the war.

After the war, industry began to expand, and many large CONGLOMERATES were formed. Unlike horizontal or vertical mergers, these companies were an amalgam of many different types of companies and as such did not fall under any of the existing antitrust laws. As a result, Congress passed the Celler-Kefauver Act in 1950, seeking to slow the growth of conglomerates. The act did not succeed in preventing their growth, however, and it was not until the Nixon administration took office in 1969 that antitrust activity again became more vigorous. Most of the focus of the administration’s policies was on protecting larger, more established companies from the predatory tactics of many of the newer conglomerates. Attempts were made or discussed, unsuccessfully, to prevent mergers among the top 200 companies so that the conglomerates could not take over the largest companies using their high prices in the stock market to acquire larger firms without using cash.

Another attempt to protect companies from predatory takeovers by conglomerates was made when Congress passed the Williams Act in the late 1960s, requiring companies acquiring more than 5 percent of another company’s stock to register with the Securities & Exchange Commission. While not able to prevent takeovers, especially hostile takeovers, the law required a waiting period of 20 days while the SEC reviewed the filing, allowing some breathing space for the target companies.

During the 1960s and 1970s, many actions were brought against a wide range of companies. Among the largest and best-known were those against the IBM Corp. and AT&T as well as actions against such smaller but well-known companies as Schwinn and the Brown Shoe Company. The case against IBM was eventually dropped, but the case against the telephone company was pressed until it finally agreed to a breakup in 1982. When it did, the Antitrust Division scored its biggest victory since the landmark cases of 1911. The case also helped establish DEREGULATION as a trend in business generally, especially during the Reagan administration after 1982. The AT&T breakup encouraged Congress to begin deregulating other protected industries, a process that continued well into the 1990s.

During the 1990s in the Clinton administration, antitrust activities began strongly again with actions against a number of companies, including Intel and Microsoft Corporation. These cases proceeded while Congress passed legislation to help deregulate other industries, notably the TELECOMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRY and the UTILITIES industry. The cases were brought both by the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission. The case against Microsoft was upheld in the courts, making it another significant victory in antitrust, although the company was penalized rather than broken up. Throughout its history, antitrust has scored notable successes and failures against companies charged with price fixing and other anticompetitive practices. Often it has been most effective in blocking mergers before they could be consummated. Once mergers have been consummated, it is more difficult to seek antitrust remedies.

Further reading

- Adams, Walter, and James Brock. Dangerous Pursuits. New York: Pantheon, 1989.

- Geisst, Charles R. Monopolies in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Kovaleff, Theodore Philip. The Antitrust Impulse: An Economic, Historical, and Legal Analysis. Armonk, N.Y.: M. E. Sharpe, 1994.

- Whitney, Simon. Antitrust Policies. New York: Twentieth Century Fund, 1958.