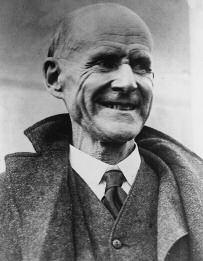

Eugene V. Debs (1855–1926) labor organizer

Eugene Victor Debs was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, on November 5, 1855, the son of French immigrant parents. At 14 he quit school to join the RAILROADS and spent several years employed as a paint scraper. Through dedication and hard work, Debs eventually rose to become a locomotive fireman, although he ultimately lost his job during the depression of the 1870s. He found new work as a grocery clerk but nonetheless maintained close contact with the railroad industry, and in 1874, he joined the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen. By now a committed labor activist, he became editor of the Firemen’s Magazine, in which he promoted social harmony through labor reform and peaceful means. In 1880, Debs’s popularity was parlayed into politics, and he was elected city clerk of Terre Haute and also briefly held a seat in the Indiana legislature. However, he remained disillusioned by railroad workers who were often bitterly divided along trade lines and sought to consolidate them to present a unified face to management. Therefore, in 1893, he helped to organize the American Railway Union (ARU) and was roundly elected its first president. Debs continued arguing for change through peaceful means, but in 1894 he was unable to prevent union members from participating in the unsuccessful Pullman strike. As the strike spread and nearly paralyzed rail commerce in the West, federal troops were eventually dispatched to put down the strike. Debs was subsequently arrested for contempt of court, and, while serving out his six-month sentence, he became exposed to the writings of Karl Marx. This proved a turning point in his political fortunes, for he formally converted to socialism. In 1898 he established the Social Democratic Party and its more famous successor, the Socialist Party of America, in 1901. Based on his own experiences, Debs also added prison reform to his progressive social agenda.

Like most socialists, Debs felt that ingrained competition between capital and labor ensured class struggle and social inequity. To him no single union could protect worker’s rights, and he argued that a cooperative commonwealth would better serve the workers than the profit system. Debs nonetheless couched his radicalism in terms of peaceful political change. In fact, he strenuously maintained that America’s traditional political values, which he strongly endorsed, were threatened by the unwillingness or inability of capitalism to promote economic democracy. He was nonetheless a fiery orator and highly popular with the rank and file, who nominated him five times to run for the presidency. In 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920, Debs ran unsuccessfully for high office, ultimately receiving only 6 percent of votes cast; as a political movement, the Socialists failed to gain broad electoral acceptance. Part of this failure was Debs’s continual struggle to unite moderate factions of the party with more revolutionary elements. However, after 1917 his reputation as a moderate was reaffirmed when he was repelled by the antidemocratic nature of the Russian Revolution and refused to join the newly emerging Communist Party.

In 1916, Debs vocally criticized the neutralist policies of President Woodrow Wilson and predicted that they would culminate in war. When the United States formally entered World War I in 1917, he was arrested for sedition under the Espionage Act and received a 10-year prison sentence the following year. He thus ran for president in 1920 from his prison cell and received nearly 1 million votes, but his political impact began to wane. Debs was released from prison under an amnesty program in December 1921, and, although in poor health, he labored to bring the discredited Socialists back to prominence. But despite large, enthusiastic crowds, the party had lost its previous appeal. He died in Elmhurst, Illinois, on December 20, 1926, a successful labor leader, a failed politician, and a forceful advocate for social change. Curiously, many of the radical positions he enunciated, such as abolition of child labor, woman suffrage, and a graduated INCOME TAX, were eventually co-opted by the political mainstream.

Further reading

- Carey, Charles W. Eugene V. Debs: Outspoken Labor Leader and Socialist. Berkeley Heights, N.J.: Enslow Publishers, 2003.

- Constantine, J. Robert, ed. Letters of Eugene V. Debs, 3 vols. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

- Debs, Eugene V. Walls and Bars: Prisons and Prison Life in the “Land of the Free.” Chicago: C. H. Kerr, 2000.

- Papke, David R. The Pullman Case: The Clash of Labor and Capital in Industrial America. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1999.

- Young, Marguerite. Harp Song for a Radical: The Life and Times of Eugene Victor Debs. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1999.

John C. Fredriksen

Tweet