The Bank of the United States history

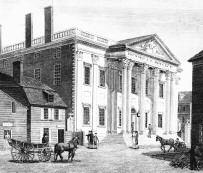

The Bank of the United States (BUS) was actually two separate banks—the First BUS (1791–1812) and the Second BUS (1817–1841). The First Bank, envisioned by Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first Treasury secretary, received its 20-year charter from Congress in February 1791. The mixed (20 percent public- and 80 percent privately owned) corporation was capitalized at $10 million, which exceeded the combined capital of all statechartered banks, insurance companies, and canal and turnpike companies of the time. Investors were permitted to tender newly issued federal bonds as payment for $400 shares in the bank, and this innovation helped to bring U.S. debt securities, which had only three years earlier sold at deep discounts, back to par. In doing so, the fledgling bank contributed to one of Hamilton’s most important achievements—restoration of the credit standing of the United States.

In the first decade of its existence, the BUS served as a safety net for the federal government, standing ready to make loans when necessitated by low tax collections. It opened branches in New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Charleston in 1792, and later in Norfolk, Savannah, Washington, and New Orleans. By 1805, half of the bank’s capital was managed by the branches. Starting with the sale of 55 percent of its shares on the open market in 1796, the federal government reduced its dependence on the bank, and the bank shifted its focus toward business lending. In the first decade of the 1800s, the bank and its branches operated essentially as a large commercial bank. It nevertheless would on occasion make specie loans to other banks when liquidity needs arose, and provided some unofficial control over note issues by regularly collecting notes of state banks and presenting them for redemption.

The establishment of a “national” bank had been a contentious political issue in 1790. At that time, those suspicious of the centralized power that such an institution might imply, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, questioned its very constitutionality. By the time that the bank was up for recharter in 1811, these abstract issues were supplemented by a distrust of foreign ownership in the bank, which had exceeded 70 percent by 1809, and questions about its economic necessity in light of large budget surpluses. The latter arguments were pivotal in Congress’s defeat of the act to recharter by the vice president’s tie-breaking vote. President Madison, bound by his ideology at the time of the bank’s founding, privately supported recharter but remained publicly neutral. The defeat forced the bank to wind up operations in 1812. As the bank had consistent net earnings of 9 percent over its 20-year existence and had declared dividends of 8 percent regularly, its closing proceeded in an orderly and timely manner. State banks quickly arose in its aftermath to assume its commercial banking functions. The strains of financing the War of 1812, however, led Congress soon to reconsider the efficacy of a quasi-central bank.

The Second BUS received a federal charter in 1816 with a capitalization of $35 million, and operated under this charter from February 1817 until March 1836. The Second Bank, like the First, was established to restore order to the currency, but also to facilitate the holding and disbursement of the government’s funds by acting as its banker. Aside from overexpanding note issues shortly after opening and a near-suspension of specie payments in 1819, the bank assumed its role effectively until 1829, when rhetoric over recharter escalated between Nicholas BIDDLE, who led the bank from 1823 until 1839, and President Andrew Jackson. Jackson was “afraid of all banks” and the possibility of default on their note issues, and was suspicious of an institution in which individuals could profit by lending the public treasure. The smoldering conflict led Biddle to seek early recharter of the bank in the latter part of Jackson’s first term. When the recharter became a campaign issue in 1832, Jackson responded by vetoing the act on July 10, 1832.

Upon reelection, Jackson ordered the removal of all government deposits from the Second Bank in 1833 and placed them with selected statechartered (i.e., “pet”) banks. With its federal charter near expiration, the bank lost much of its regulatory zeal, allowing the pet banks to use the new deposits to expand note issues. With no impending threat of note redemption by the BUS, these issues combined with inflows of specie from abroad to produce a rapid inflation between 1834 and 1836 that ended in the financial Panic of 1837. In the meantime, the Second BUS obtained a state charter from Pennsylvania in 1836 and continued operations until 1841. As bank president and still the nation’s most influential banker, Biddle actively criticized Jackson’s 1836 policy of requiring specie payments for the purchase of public lands, mostly in the West, to curb speculation, and even made unsolicited and apparently unwelcome attempts to steer President Van Buren away from the impending crisis immediately after Jackson left office in the spring of 1837. In the aftermath of the panic, “Biddle’s Bank” used its resources and international reputation to engage in active speculation in the cotton market, and heavy losses from these activities contributed to a second financial panic in 1839. The bank’s capital stock appears to have been a total loss when the doors closed on February 4, 1841.

When the Whigs regained the White House in 1841, Henry Clay quickly moved an act to charter a third bank through Congress, but it was vetoed unexpectedly by President John Tyler, who ascended to office after President Harrison’s death shortly after inauguration. The nation’s central banking “experiment” would not be again attempted until the founding of the Federal Reserve in 1913.

Further reading

- Catterall, Ralph C. H. The Second Bank of the United States. 1903. Reprint, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

- Hammond, Bray. Banks and Politics in America. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Smith, Walter Buckingham. Economic Aspects of the Second Bank of the United States. New York: Greenwood Press, 1953.

- Taylor, George Rogers. Jackson versus Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States. Boston: D. C. Heath, 1949.

Peter L. Rousseau