Nicholas Biddle (1786–1844) banker, legislator, and diplomat

Born in Philadelphia, Biddle was the son of a Philadelphia banker. Recognized as a child prodigy, he entered the University of Pennsylvania at age 10 and was scheduled for graduation at 13. Because of his age, he was not granted a diploma and so enrolled at the College of New Jersey in Princeton, graduating as valedictorian at age 15. He then returned to Philadelphia to study law with his brother William and jurist William Lewis. In 1804, he became secretary to John Armstrong, the ambassador to France. Adding to his resume, he also helped work on the details of the Louisiana Purchase and attended Napoleon’s coronation.

Biddle also served as secretary to James Monroe, the new ambassador, in 1807. He later edited the papers of Lewis and Clark but abandoned the effort when he was elected to the Pennsylvania legislature in 1810. He also founded the literary journal Port-Folio. During the War of 1812, he served on the Philadelphia Committee on Defense and twice ran unsuccessfully for Congress. He also served in the Pennsylvania legislature, where he became familiar with the BANK OF THE UNITED STATES. He was appointed to the bank’s board of directors by Monroe in 1819, and when Langdon Cheves resigned, he was appointed president of the bank in 1822. He remained its president for the next 14 years.

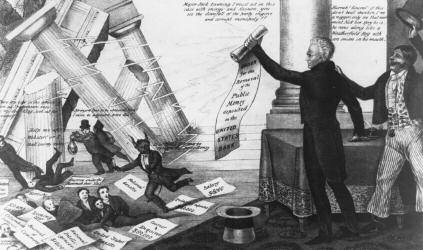

The bank was heavily influenced by his leadership, and it became known as “Biddle’s Bank,” a nickname that later did not sit well with President Andrew Jackson. During the 1820s, the bank was very successful, and the economy grew under Biddle’s guidance. Biddle helped transform the bank, which previously had been a Philadelphia bank with branches throughout the East and South, into a central bank. He used the bank to effectively counter trends within the economy, providing liquidity when there appeared to be business slowdowns and contracting it when the economy expanded. But after the election of 1828, when Andrew Jackson took office, the new president believed the bank was unconstitutional despite an earlier Supreme Court ruling in MCCULLOCH V. MARYLAND in 1819.

Congress reauthorized the bank in 1832, but Jackson vetoed the bill. After Jackson refused to renew the bank’s charter, Biddle remained with it for several years until it eventually closed its doors. It later changed its name to the Bank of the United States of Pennsylvania. He finally resigned from the greatly diminished institution in 1839. He was later charged with fraud but eventually acquitted of all charges.

The failure of the Second Bank of the United States was due in part to Biddle’s inability to deal with the politics of Jackson, who once told him that “I do not dislike your bank any more than all banks.” There was some animosity on the president’s part toward wealthy men of letters, of whom Biddle was the best example of his generation. The animosity had a distinct downside since the United States was left without a central banking institution until the FEDERAL RESERVE was created in 1913. The vacuum left by the failure of “Biddle’s Bank” was filled by private bankers in later years, notably by John Pierpont Morgan, whose power and influence finally led to the establishment of a true central bank almost a hundred years later.

Further reading

- Catterall, Ralph C. H. The Second Bank of the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1903.

- Govan, Thomas P. Nicholas Biddle: Nationalist and Public Banker, 1786–1844. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959.

- Taylor, George R. Jackson v. Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States. Boston: D. C. Heath, 1949.

- Wilburn, Jean A. Biddle’s Bank: The Crucial Years. New York: Columbia University Press, 1967.